Escape from Wandsworth prison

Explaining the background to a serious security breach

On 6 September 2023, it emerged that a man had escaped from Wandsworth prison in southwest London.

The government announced that an independent inquiry will investigate the incident. We await the findings.

In response to the many media inquiries that we have received, we have created a dedicated page on our website to help people find out more about Wandsworth and the prison system more generally.

Escapes from prison are rare

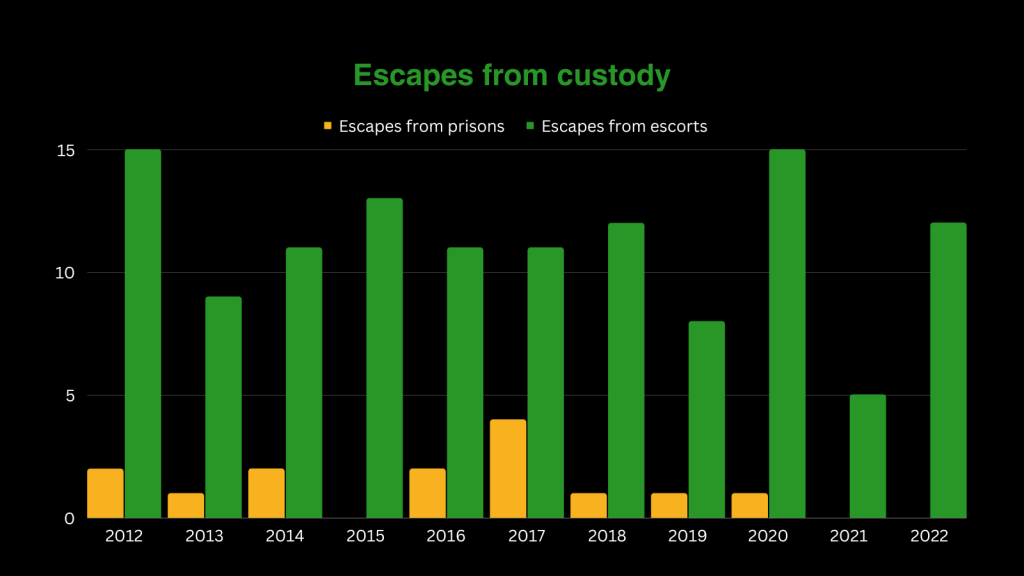

Cases of this nature are unusual in England and Wales; this is only the fourth time since 2017 that someone has escaped from a prison.

As the chart below shows, escapes from vehicles escorting people between prisons and courts are slightly more common, but still rare.

Wandsworth prison has been under significant pressure for a long time

Wandsworth is one of the most overcrowded prisons in England and Wales. Official figures published by the Ministry of Justice show that it has room for 950 men in safe and decent accommodation, but at the end of August 2023 it was being asked to hold 1,617.

The prisons watchdog, His Majesty’s Inspectorate of Prisons, visited Wandsworth in September 2021 and found that “[t}here were not enough staff to make sure prisoners received even the most basic regime”.

In his report of that inspection, the Chief Inspector of Prisons, Charlie Taylor, wrote: “One group of prisoners from Trinity Unit, who came blinking into the sunlight, told me that it was the first time they had been outside for more than a week.”

When inspectors returned to Wandsworth in June 2023, they found that more than half the men had no work to do. These men spent 22 hours a day locked inside their cells. Violence had increased.

Wandsworth is one of many prisons struggling with chronic overcrowding and staff shortages

The most recent inspectorate report on Wandsworth was published in July 2023. It was one of several concerning prison reports to appear within just a six-week period. Reports on Bristol, Leeds and Lowdham Grange prisons all raised similar issues and serious concerns.

Only a week before the escape from Wandsworth, the Chief Inspector wrote to the Secretary of State for Justice, Alex Chalk, to call for immediate action to improve another prison – Woodhill, in Buckinghamshire – where more than 800 self-harm incidents had been recorded in the past 12 months.

Two days after the escape was reported, official prison population figures showed that 77 of the 120 prisons across England and Wales were holding more people than they were designed to accommodate.

Journalists are becoming increasingly aware of the problems inside prisons

Prisons are out of sight, and usually out of mind. But the escape from Wandsworth has brought the issues in the system out into the open – in newspapers and on radio and television (including a discussion on the ITV show This Morning).

The Times‘ coverage of the escape included detailed analysis of the system, under the heading: “Security and personnel issues, violence and overcrowding . . . the problems facing the sector in the UK are legion.”

In its leading article, the newspaper stated: “[T]he overall picture in Britain’s prisons is bleak. Living conditions are often inhumane and unsanitary, levels of rehabilitation unsatisfactory, and prison officers are both inexperienced and overstretched following years of cuts.

“It is all very well talking tough on crime and boasting about repairs to cuts in police numbers. But prisons are an equally critical component of the justice system.”

In a newsletter to its readers, the Guardian took an in-depth look at prisons. It revealed how the number of people in prison had risen by almost 6,000 in the past 12 months.

“Wandsworth prison life: Decay, drugs and drudgery” was the headline above a feature article on the BBC News website about the challenges inside London’s most overcrowded jail.

The Spectator carried an article with the headline “A Wandsworth prison jailbreak was waiting to happen”. Its author, David Shipley, wrote: “During my time at Wandsworth the prison often ‘locked down’ because the ‘count’ of inmates on a particular wing showed men were missing.”

Even the Sun called for action: “Wandsworth jail is a filthy shambles, under-manned by guards whose morale is at rock-bottom.

“Justice Secretary Alex Chalk has to turn it around – along with all our overcrowded, cesspit prisons – and improve staff retention across the service.”

So, where do we go from here?

The escape from Wandsworth, and the authorities’ response to it, has shown that problems inside prisons spill out into the towns and cities around them.

The sensible way to protect the public is to ease pressure on a system that has been asked to do too much, with too little, for too long.

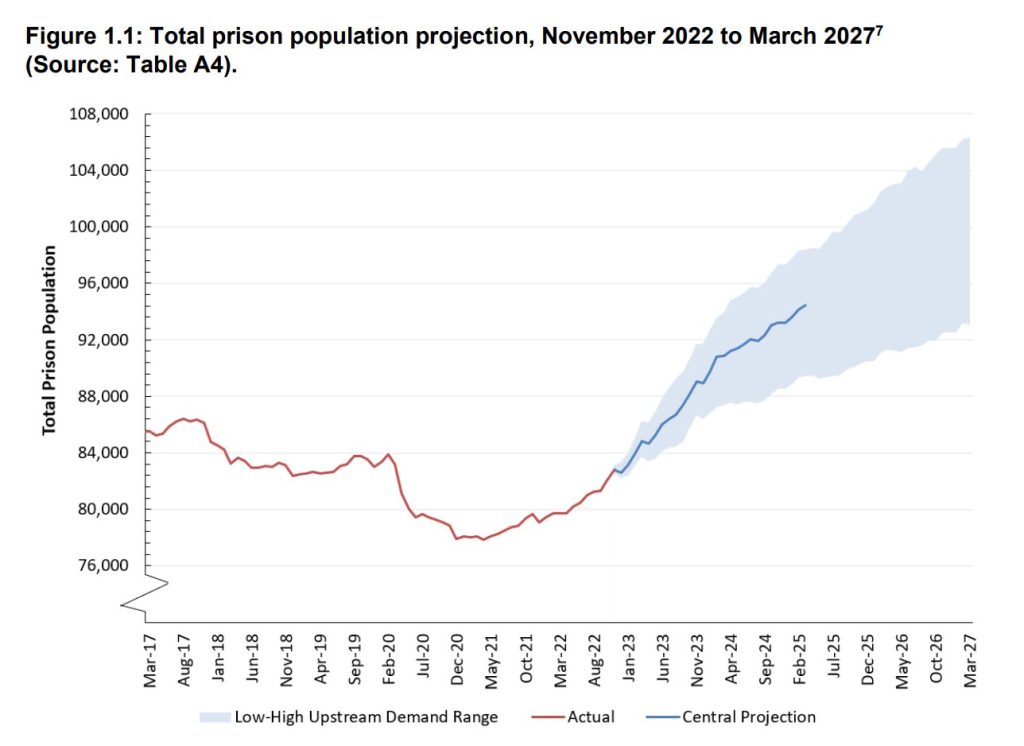

The Ministry of Justice’s own projections indicate that the prison population could rise to as high as 106,300 by March 2027.

In March 2021, it stood at 78,058. This would be a 36% increase in just six years.

The government wants to build more prisons, which, if approved by planning authorities, would be among the largest jails in the country.

But there are many problems with these plans, including the fact that there are insufficient staff to run the prisons we already have.

Reducing the prison population makes more sense, not least because the government’s own research indicates that short prison sentences are less effective than community sentences at preventing reoffending.

Something has to give

If politicians, journalists and commentators are serious about the need for prison reform, they must consider the decisions that led us to this point and prepare for a sensible conversation about who we incarcerate and for how long.

A starting-point for that conversation could be the IPP scandal. A report published by the Prisons and Probation Ombudsman examines lessons learned from its investigations into the self-inflicted deaths of 19 people who were sent to prison under the unjust – and now abolished – sentence of imprisonment for public protection (IPP).

The IPP sentence was scrapped more than 10 years ago, but almost 3,000 people who were given it remain in prison today. About half of them have never been released; the rest have been released but then recalled.

The ombudsman’s report reveals that at least 78 people on IPP sentences have died, in circumstances recorded as self-inflicted, since 2005. We are proud to have supported UNGRIPP in drawing attention to this injustice.

If you would like to know how you can help to put things right, please consider joining the Howard League as a member.

-

Join the Howard League

We are the world's oldest prison charity, bringing people together to advocate for change.

Join us and make your voice heard -

Support our work

We safeguard our independence and do not accept any funding from government.

Make a donation