Treasures from the Howard League Collection

Archived documents offer an insight into the work of the Howard Association and the Penal Reform League

When, in 1920, the first women to become magistrates began to take their seats in court, they were greeted with a letter and welcome pack from two of the country’s leading penal reformers – Margery Fry, a magistrate herself and Secretary of the Penal Reform League, and Cecil Leeson, Secretary of the Howard Association.

“The appointment of women as magistrates,” the letter stated, “is one of the reforms which the Howard Association and the Penal Reform League have for long been advocating. We believe that its achievement will mark the beginning of a new spirit in our criminal administration.

“May we ask your consideration, at the moment of entering your new duties, of the enclosed literature. We shall be glad to give you any further information you may wish for as to the aims of our two societies, which are working in close co-operation, and will probably shortly be definitely united.”

And “definitely united” the two societies were, a few months later. The Howard Association, founded in 1866, and the Penal Reform League, set up in 1907, officially joined forces in 1921 to become the Howard League for Penal Reform.

Now, 100 years on, the charity still plays a key role in the life of the nation, drawing on its research and expertise, and offering informed advice to magistrates, judges, police, politicians and all who wish to see less crime and safer communities.

The joint letter to new magistrates from 1920 is among thousands of treasures that can be found in the Howard League Collection, an archive kept in the Modern Records Centre at the University of Warwick. Photographs from the collection can be viewed here.

As we mark the centenary of the historic merger, we have delved into the archive to see what this unique collection of documents tells us about the early activities of the Howard Association and the Penal Reform League, and how they are reflected in the important work carried out by the Howard League today.

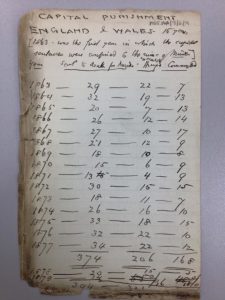

Good examples can be found among some of the oldest documents in the collection. Just as the Howard League monitors prison statistics today, so did the Howard Association in the late 19th century. Handwritten tables contain records of executions, crime figures, rates of imprisonment, and how numbers in Britain compared with other jurisdictions across Europe.

In much the same way that the Howard League visits prisons today, the Howard Association kept records from its own travels to jails across the country. Handwritten notes from journeys to Chelmsford, Birmingham and Winchester prisons can all be found in the archive, as well as a letter to a newspaper from Howard Association Secretary, William Tallack, giving a detailed account of a trip to Dartmoor prison in 1896:

“Then we were shown the washhouses, where once a fortnight the prisoners have the privilege of a good bath…On the ground floor we were shown into the punishment cells. These were exceedingly bare, vault-like structures, and the unfortunate individuals who are confined therein must have a terrible time of it, being in semi-darkness, and shut off from the rest of the prison by no less than two doors and a gateway, which are kept locked.”

Another treasure from the collection is the scrawled diary entry made by Howard Association Secretary, Edward Grubb, following a 1904 visit to Washington DC, where he met US President Theodore Roosevelt.

Being granted an audience at the White House was no mean feat, but as Grubb noted, the meeting was brief: “The whole interview cannot have lasted two minutes. I am very glad to have had it, and to see how entirely simple and unconventional American democracy is. It was impossible to feel nervous – everything was so wholly plain and ordinary.”

Several documents shed light on early successes for the Howard Association and Penal Reform League, not least the appointment of probation officers – an advance for which both charities had campaigned.

In a letter to the Times, published in 1904, Grubb wrote: “I venture to think that the appointment of probation officers, paid by the State, is one of the reforms most urgently needed in our criminal procedure at the present time.”

This view was supported two years later by Grubb’s successor as Secretary, Thomas Holmes, in a letter to the Daily News.

Holmes wrote: “The Howard Association heartily endorses the appointment of probation officers, recognised by the Home Office and under the control of the magistrates at our Police Courts. The appointment of such officers with defined legal powers would enable our magistrates to adopt other means than the usual committal to prison. Were such officers appointed the principle of restitution or reparation to the injured might with great advantage be adopted.”

Holmes, a former police-court missionary, added: “Nothing but evil can follow if young people are familiarised with prison at the age of sixteen.

“During my police court missionary days I have seen many adults, male and female, consigned to prison because they were unable to pay at the moment fines varying from three shillings to a pound.”

In 1913, the sixth annual report of the Penal Reform League gave a “belated welcome” to the National Association of Probation Officers, which had been founded the previous year.

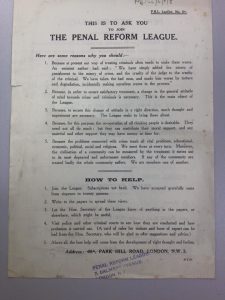

This report can be found in the collection, along with a Penal Reform League recruitment pamphlet from that decade. The pamphlet’s long list of reasons to join the society ended with: “Because the problems connected with crime touch all vital problems, educational, economic, political, social and religious. We meet these at every turn.

“Moreover, the civilisation of a community can be measured by the treatment it metes out to its most depraved and unfortunate members. If any of the community are treated badly the whole community suffers. We are members one of another.”

After the merger, the Howard League was able to point to a number of small victories from its first year as a single organisation. These were listed in its first annual report:

*Arrangements are now being made by which minor repairs to a prisoner’s own clothes and boots can be carried out in the prison in preparation for his release…

*Special attention is now being paid to the whole question of providing a shave for those men who desire it when leaving prison or appearing in court.

*Pregnant women in prison are now allowed to prepare the clothes for their expected babies.

*In most prisons, a routine visit to the lavatory is now arranged in the evenings.

*Prisoners on punishment are no longer deprived, as a general rule, of their exercise.

These were small steps, and we are celebrating the centenary because things have improved. The Howard League was one of the first non-governmental organisations to be given consultative status with the United Nations. It worked to abolish capital and corporal punishment, to raise the age that children could be incarcerated, and helped to set up the compensation scheme for victims of crime.

More recently, the charity has worked with police to reduce arrests of children by more than 70 per cent over the last decade, helping to give hundreds of thousands of children a brighter future.

There is still much more to do, and the story does not end here. But the treasures of the Howard League Collection reveal how it all began.

-

Join the Howard League

We are the world's oldest prison charity, bringing people together to advocate for change.

Join us and make your voice heard -

Support our work

We safeguard our independence and do not accept any funding from government.

Make a donation