Why are prisons overcrowded?

Explaining the problems in the prison system, how they arose, and how we might solve them.

Prisons in England and Wales face an overcrowding crisis of unprecedented proportions.

By the prison service’s own measure of safe and decent accommodation, there were fewer than 80,000 prison places in March 2025.

But the number of people in prison stood at almost 88,000, and official population projections indicate that it will continue to rise.

The situation has become so severe that the Ministry of Justice (MoJ) has resorted to emergency measures to ease pressure on the system.

In October 2023, the MoJ introduced a scheme that allowed some people to be released from prison up to 18 days early under supervision. In March 2024, the scheme was extended to enable releases up to 60 days early. In May 2024, it was extended again, to allow for releases up to 70 days early.

After Labour came to power in July 2024, the new Lord Chancellor and Secretary of State for Justice, Shabana Mahmood, announced that the early release scheme would end. Instead, she announced that the government would temporarily reduce the proportion of custodial sentences served in prison from 50% to 40%, a policy measure that had been recommended by the Prison Governors’ Association. This scheme began in September 2024.

Explaining why she was taking steps to reduce the prison population, Shabana Mahmood said: “There is now only one way to avert disaster.”

The video above presents a clip from an interview we gave to the Today programme on BBC Radio 4 in May 2025 – one of many enquiries about this issue that we have received from journalists, politicians and the public.

In response to the high level of interest, we have created a dedicated page on our website to explain what the problems are, how they arose, and how they might be solved.

When will we run out of prison space?

Technically, we have already; the prison system is being asked to accommodate more people than it is designed to hold.

Why, then, do we often see headlines claiming that the prison system is “almost full” or that there are only a few hundred “places left”? The answer lies in how prison population statistics are recorded and reported, which can lead to confusion.

The total number of people in prison is updated weekly in a regular statistical bulletin published by the MoJ. This bulletin tells us how many people are being held in men’s prisons and how many are in women’s prisons. It also provides comparative figures for the previous week and the previous year, so we can see if the population has risen or fallen.

But overcrowding data is published only once a month, when the MoJ releases a more detailed bulletin with population figures broken down for each prison in England and Wales. This is where it gets complicated…

For each prison, the MoJ publishes four figures:

Population. This is the number of people held in the prison.

Baseline Certified Normal Accommodation (CNA). This is the number of places in the prison, according to the prison service’s own measure of accommodation; as the MoJ puts it, “CNA represents the good, decent standard of accommodation that the service aspires to provide all prisoners”.

In-Use CNA. This is the baseline CNA figure, but without places that are not available for immediate use, such as cells that are damaged or affected by building works.

Operational Capacity. This figure, which is decided by prison group directors, is “the total number of prisoners that an establishment can hold taking into account control, security and the proper operation of the planned regime”.

When a prison’s operational capacity is higher than its CNA, it is usually the case that people are being made to share cells that are designed for one person. In some cases, three people will share cells designed for two.

The Howard League analyses the scale of prison overcrowding each month. We use the CNA figure for each prison as this is the prison service’s own measure of safe and decent accommodation. It is the number of people that the prison is designed to hold.

But even this description is a bit misleading: as we will go on to explain later in this article, some of the cells that people are being crammed into are simply unfit for human habitation.

At the end of February 2025, more than half of the prisons in England and Wales were holding more people than their CNA. The most overcrowded jail was Durham, which had a CNA of 561 but was being asked to accommodate 979. (Up-to-date population statistics for each prison can be found here.)

The prison system is beyond full. When politicians and journalists say that it is “almost full”, it is usually because they are quoting the operational capacity figure, which can be moved up or down at the discretion of senior prison officials.

Why does it matter if prisons are overcrowded?

When a prison is asked to accommodate more people than it is designed to hold, it piles more pressure on people working there and makes it harder to meet the needs of people living there.

If someone is sent to prison, we should do all that we can to help them to turn their life around and move on from crime. But overcrowding, coupled with chronic staff shortages, makes it more difficult for prisons to engage everyone in activities that help rehabilitation, such as exercise, education, employment and training.

For many people, this means being locked in an overcrowded cell for 23 hours a day with nothing to do, at a time when the physical state of prisons is getting worse.

In October 2023, the Ministry of Justice confirmed that it had stopped all “non-essential maintenance work” because prisons were simply too crowded to allow for the closure of cells that such work would entail.

Worse still, official inspection reports reveal that people are being placed in cells that are not fit for purpose.

Rules state that all cells must be certified by the government as being “adequate for health” in terms of their size, lighting, heating, ventilation and fittings. If cells are not adequate for health, then they must be either fixed immediately or withdrawn from use.

As overcrowding pressures continue, however, it is becoming increasingly clear that cells are being certified as adequate when they are not.

In May 2024, we blogged about delays in constructing a new unit to replace the dark, damp and dilapidated cells in the segregation unit in Bedford prison, which inspectors have branded a “disgrace”. (The blogpost also mentions “crumbling infrastructure” in Lewes prison, a rat infestation in Pentonville prison, flies in Brinsford prison, and incidents in Winchester prison where men were able to dig through a wall using simple implements such as plastic cutlery.)

We are also concerned about some cells in Whatton prison, which are too small but have been certified as adequate for health. The cells are so small that the toilet, which is unscreened, is positioned directly next to the head of the bed. There is not enough room to move about, sit down or eat meals, and some of the cells are so poorly ventilated that they have become mouldy.

The growing tension behind bars is reflected in official statistics, which reveal worrying rises in self-harm and violence.

Prisons in England and Wales recorded more than 70,000 incidents of self-harm in 2023 – at a rate of one every seven-and-a-half minutes. Assaults rose by 28% to almost 27,000 – a rate of one every 20 minutes.

Where incidents require police investigations or referrals to hospitals for treatment, they put further strain on local public services.

Overcrowding makes it harder to respond effectively to major incidents. When prisons have run into serious trouble in the past, such as the riot in Birmingham prison in 2016 or the catastrophic deterioration in conditions in Liverpool prison in 2017, officials have reacted by moving hundreds of people to other jails to ease pressure. When overcrowding becomes so severe that more than half of prisons are holding more people than they are designed to accommodate, moving large numbers from prison to prison is not an option.

The MoJ has resorted to increasingly desperate measures to find space in the prison system. Temporary “rapid deployment cells”, which have a lifespan of about 15 years, have been installed on some prison sites.

As well as the introduction of an early release scheme and a pause in prison maintenance work, we have seen police cells being used to hold people who would be in prison.

Draft legislation that would have given ministers the power to move people to prisons abroad was dropped when Parliament was dissolved before the 2024 general election.

How did we get into this mess?

These problems did not come out of the blue. In 2014, we published a briefing called Breaking Point, which revealed that 78 prisons were holding more people than they were designed to accommodate. We wrote: “Urgent action is needed to ease the strain on the prison system. The MoJ must take action to reduce the prison population and increase prison officer numbers.”

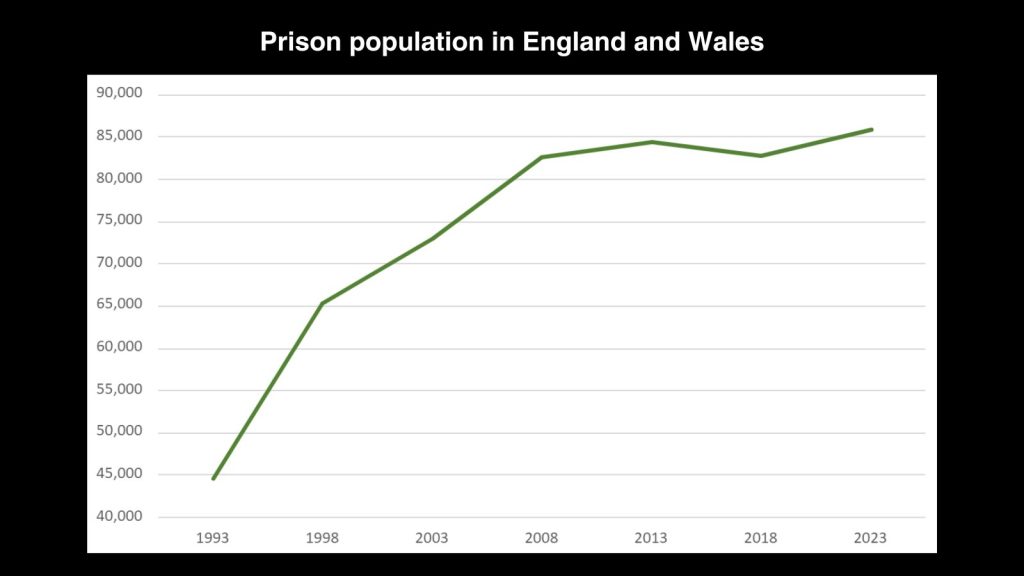

The prison population has almost doubled in the last 30 years. After a rapid increase in the 1990s and 2000s, it began to stabilise in the 2010s and decreased slightly during the Covid-19 pandemic, but it has since risen again to reach record heights.

This is not a response to rising crime – in fact, recorded crime has fallen – but a sign of how changes in sentencing policy, led by politicians, have had a dramatic impact. Prison sentences have been handed down more and more, and they have got longer and longer over time.

Campaigns calling for the creation of new offences, or the introduction of longer sentences, to address specific issues or problems have contributed to this shift. The impact of these campaigns can be far-reaching – when politicians make sentences longer for one crime, it often leads to calls for longer sentences for other crimes. And so it goes on.

A backlog of cases in the courts, which grew longer during the Covid-19 pandemic, has not helped. The number of people in prison on remand – awaiting trial or sentence – has reached its highest level for at least 50 years.

Meanwhile, the number of people who have been recalled to prison after being released has also reached a record high. Prisons overwhelmed by overcrowding are not preparing people for life outside, and there is insufficient support for people when they are released. Too often, we see people leaving prison without somewhere to live.

The prison population in England and Wales is the highest in Western Europe.

Why don’t we just build more prisons?

We have been down this road before. When governments have faced overcrowding pressures in the past, their instinctive response has been to promise to build more prisons.

But it is like trying to ease traffic congestion by adding an extra lane to a motorway – it takes years to finish and, when it is done, it draws more cars and leads to even bigger traffic jams.

When the prison system gets bigger, the problems within it get bigger, becoming harder to solve. And it makes no sense to build new jails when there are too few staff to run the ones we already have.

Many stories about the prison system focus on the failings in jails built during the Victorian era, but official inspection reports reveal that there are challenges in newer ones as well.

Lowdham Grange prison, which opened in 1998, was found to be so unsafe in May 2023 that the government had to take over the running of it.

A January 2024 inspection of Five Wells prison discovered that almost 750 officers had been hired since it opened in 2022, but only 272 remained in post.

In February 2024, inspectors noticed “slow but perceptible decline” in Buckley Hall prison, which opened during the 1990s.

Problems in prisons spill out into the towns and cities around them, and new jails put added strain on local public services. It should surprise no one that proposals to build more prisons have met significant opposition from residents living nearby.

The MoJ’s own data shows that community sentences are more effective than short prison sentences at reducing crime. When probation services are overburdened and underfunded, it makes no sense to waste resources on unwanted prison plans and lengthy planning inquiries.

What should we do instead?

It is time for a different approach. Responding to crime effectively – or, better still, preventing it happening in the first place – requires difficult decisions, and no one should pretend that these are easy. But it has never been clearer that a change of direction is needed and, the longer we leave it, the harder it will be.

During the 2024 general election campaign, the Prison Governors’ Association took the unprecedented step of writing to all the main party leaders, warning that “it is a matter of days before prisons run out of space, and that the entire Criminal Justice System (CJS) stands on the precipice of failure. Within a matter of weeks, it will put the public at risk.” They recommended that automatic early release for standard determinate sentences should be moved so that people are released at the 40% mark of their sentence – a policy move that has since been adopted by the government.

This move helps to alleviate the immediate crisis in capacity but it still leaves the prison system overcrowded and liable to future shortages of capacity. A range of further measures must be looked at, from introducing a presumption against short prison sentences to reforming the overuse of remand. In May 2025, the government announced plans to make more use of fixed-term recall to free up spaces in prison.

Our briefing, Grasping the nettle, offers ministers a range of policy options that could deliver a lasting solution..

For too long, criminal justice policies have been judged on whether they appear “tough” or “soft”, when what really matters is whether they work. We can start to put things right if we shift our focus from punishment to problem-solving. If someone needs support to move away from crime, they will have better access to the services that can help them if they are being supervised in the community than if they are locked in a prison cell for hours on end with nothing to do.

Making sentences longer and longer puts intolerable pressure on the prison system and creates bigger challenges that will have to be tackled sooner or later. Dealing with the consequences takes valuable resources away from preventing crime and supporting victims.

Common sense tells us that someone is much less likely to be involved in crime if they have a settled home and steady employment. Imagine what we could achieve if we stopped building prisons and invested in homes, schools, hospitals and jobs instead.

Want to know more about the prisons crisis? Read our explainer on sentence inflation.

-

Join the Howard League

We are the world's oldest prison charity, bringing people together to advocate for change.

Join us and make your voice heard -

Support our work

We safeguard our independence and do not accept any funding from government.

Make a donation